There are things my daughters say that make me feel proud to be their dad. From my 7-year-old:

“I have a lot of stuff. For my birthday party, can I ask each of my friends for a toonie instead of a present? I’m going to give the money to the SPCA.”

“Dad, that new song by The Sheepdogs sounds a lot like The Black Keys, don’t you think?”¹

There are also things my daughters say that make me feel proud to be their mathteacherdad.

One day this week, we were talking math at the dinner table.

Being in Grade 2, Gwyneth is not yet learning about multiplication at school. However, her best friend knows about “timesing,” so she is curious and motivated. We’ve been discussing multiplication in terms of groups of. Don’t worry, we’ll have conversations about arrays later. Dropping in, mid-conversation:

Being in Grade 2, Gwyneth is not yet learning about multiplication at school. However, her best friend knows about “timesing,” so she is curious and motivated. We’ve been discussing multiplication in terms of groups of. Don’t worry, we’ll have conversations about arrays later. Dropping in, mid-conversation:

Me: What do you notice?

Gwyneth: Two groups of three is the same as three groups of two.

At this point, I could have said, “That’s right. Changing the order doesn’t change the answer.” I didn’t. Being a math teacher and her dad, I also could have said, “That’s because multiplication is commutative, Sweetie.” I didn’t.

Me: What about three times five and five times three?

Gwyneth: Three groups of five is … fifteen.

Me: How do you know?

Gwyneth: Well, two groups of five is ten and one more group makes fifteen.

Me: Okay, so what about five times three?

What she said next, after a brief pause, blew me away.

Gwyneth: Nine and six make fifteen.

Me: How did you get that?

Gwyneth: I took one away from six to make ten and …

Me: No, I get that. I mean where did the nine and the six come from?

Gwyneth: Well, three groups of three is nine and two groups of three is six.

I was asking my daughter questions to have her explore the commutative property and she drops the distributive property into our conversation! Any English teachers still reading this blog after my last post may question my use of an exclamation mark. Math teachers will not. Gwyneth understands, conceptually, that 5 × 3 = (3 × 3) + (2 × 3).

I asked her to draw this for me. She drew five groups of three dots.

Gwyneth: Three, six, nine, twelve, fifteen.

Me: Wait! What about the nine and the six?

Gwyneth: I said those. Three, SIX, NINE.

Me: Yeah, I heard you. But, before, you ADDED the six and the nine.

Gwyneth: Dad, I’ve got LOTS of strategies.

I was so proud to hear her say this that I didn’t even mind the eye-rolling.

In his book The Joy of x, Steven Strogatz writes about the counterintutiveness of the commutative law.

Whereas it is intuitive to Gwyneth that adding five to three should be the same as adding three to five, it is not intuitive to her that having three groups of five should be the same as having five groups of three.

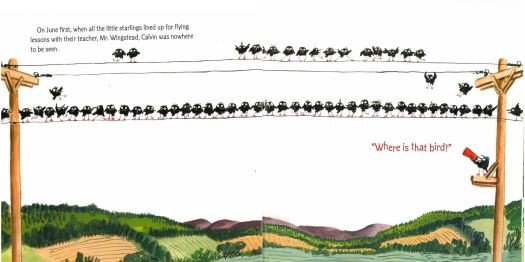

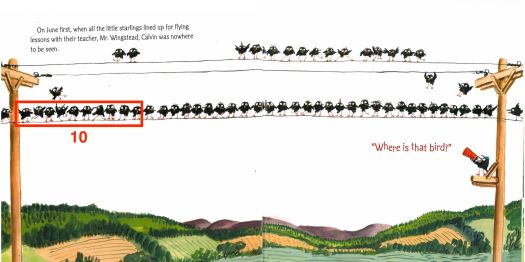

Why is 5 + 5 + 5 …

… obviously the same as 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 + 3?

Strogatz makes the point that if we visualize 3 × 5 as a rectangular array with 3 rows and 5 columns …

and turn this picture on its side giving us 5 rows and 3 columns, or 5 × 3, …

and turn this picture on its side giving us 5 rows and 3 columns, or 5 × 3, …

then 3 × 5 must equal 5 × 3. The commutative law becomes more intuitive.

then 3 × 5 must equal 5 × 3. The commutative law becomes more intuitive.

Strogatz, a frequent guest on Radiolab, goes on to give examples of real-world situations in which people forget, or refuse to accept, the commutative law.

Once again, I have taken a page out of Christopher Danielson’s playbook with this post.

¹ I just learned that The Sheepdogs’ album was produced by The Black Keys’ Patrick Carney. Impressive kid, eh?