Last week, Nancy Allan, Manitoba’s Education Minister, announced the province’s revised back to basics math curriculum. The move was applauded in a Winnipeg Free Press article.

So, why the changes? From the Winnipeg Free Press: “I heard from parents that their kids were lacking basic arithmetic skills,” Allan said. “It was during the (2011) election, and I picked this up on the doorstep.”

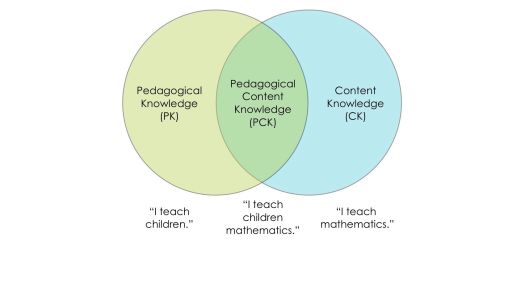

What we know about how children learn mathematics is no match against a politician with a political football. Allan spent “two years of serious work with [the province’s] education partners. We have met with all the math professors, the superintendents have been part of this.” Notably absent from the list: math educators, faculties of education.

The bottom half of the internet gives us a glimpse of Allan’s doorstep. I could have saved her those two serious years. Rather than a revision, her “kids these days” constituents could have been placated with the addition of one prescribed learning outcome, one PLO to rule them all:

Students will be able to make change.

Where an appeal to logic has failed the reform movement, an army of pimply-faced cashiers able to count back change to John Q. Public – even after he’s thrown down an extra nickel after the fact – might just succeed. Of course, this skill involves applying the mental math strategy of thinking addition for subtraction, not the standard subtraction algorithm. But let’s not tell them that.

The Winnipeg Free Press article featured a poll asking readers “Which of these everyday math tasks could you tackle without a calculator?”

Two of my favourites:

- Determine how much you should leave for a 20% tip at a restaurant.

14% (6192 of 45357 votes) - Halve a recipe that calls for 2/3 of a cup of an ingredient.

12% (5577 of 45357 votes)

The results are interesting in light of the following: “The minister said the revised curriculum makes Manitoba the first province in Western Canada to go back to placing an emphasis on basic skills previous generations had.” At best, it looks like previous generations have misplaced those basic skills. At worst, they never had ’em. Psst, hey kids… remember this the next time your uncle quizzes you with “What’s 7 times 8?” He may be asking because he doesn’t know.

So, what happened? Previous generations learned to do math, by definition, “the old way.” They were taught the standard pencil and paper algorithms. In the two tasks above, the standard algorithms are far from efficient. In the first task, a more efficient strategy is to divide by ten and double. In the second task, it’s two thirds of a cup… two thirds… twoOOOoooOOOooo thirds.

Buried in the announcement: “Allan said the province will provide parents with a website to help them understand what their kids are learning.” Admirable. But its necessity is an indictment of the parent’s, not the child’s, mathematics education. Not many politicians are going to pick that up on the doorstep.

Recommended: Dr. Keith Devlin’s response to a recent New York Times article

Update: Frank beat me to it.

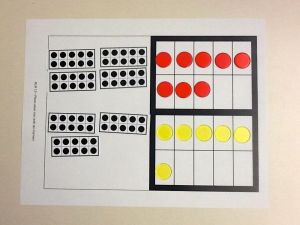

December 10, 2013: From a Grade 4 WNCP approved textbook, no less: