How can technology be best used as a tool for learning mathematics? Calculators can assist with computations when learning other mathematics. iPads can help students communicate their learning. I’m asking about something else. I’m asking about the use of technology to develop new mathematical understandings.

Last week, Marc and I explored this question with about twenty math department heads. First, teachers were given time to explore several dynagraphs. In this version, the equation of each function was hidden. This became the problem to solve.

Following this activity, we wanted to discuss the question above. One approach would be to present several different examples and evaluate each, sharing our criteria. Not very effective. It’s our evaluation, our criteria.

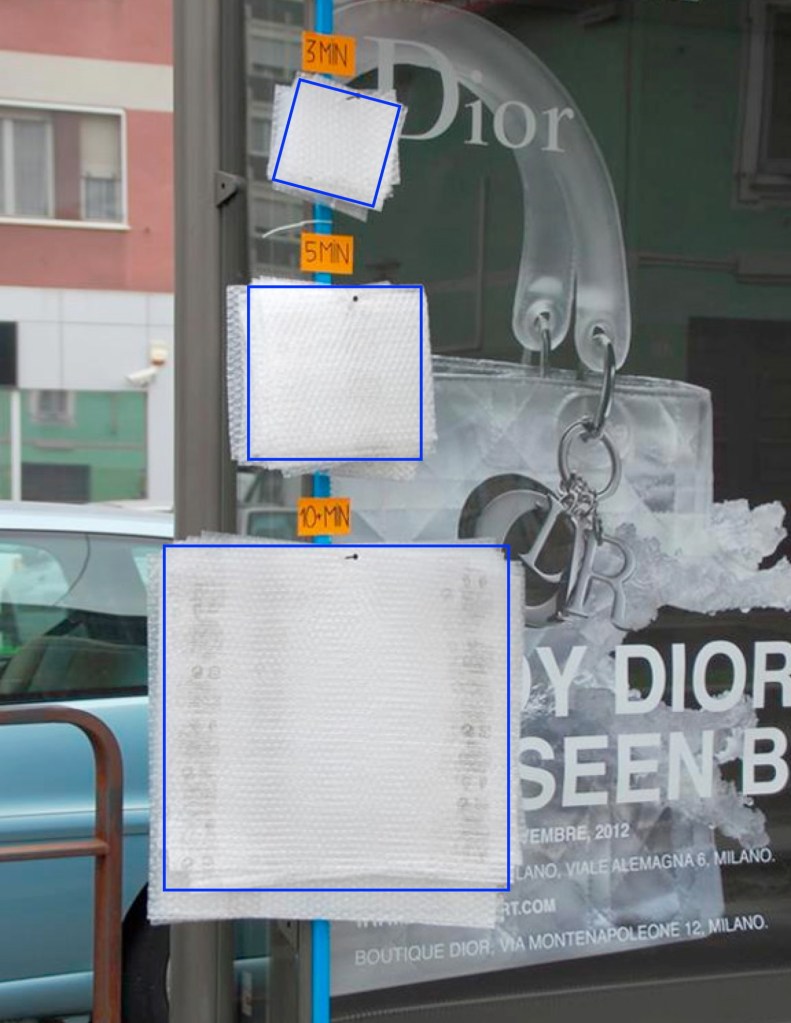

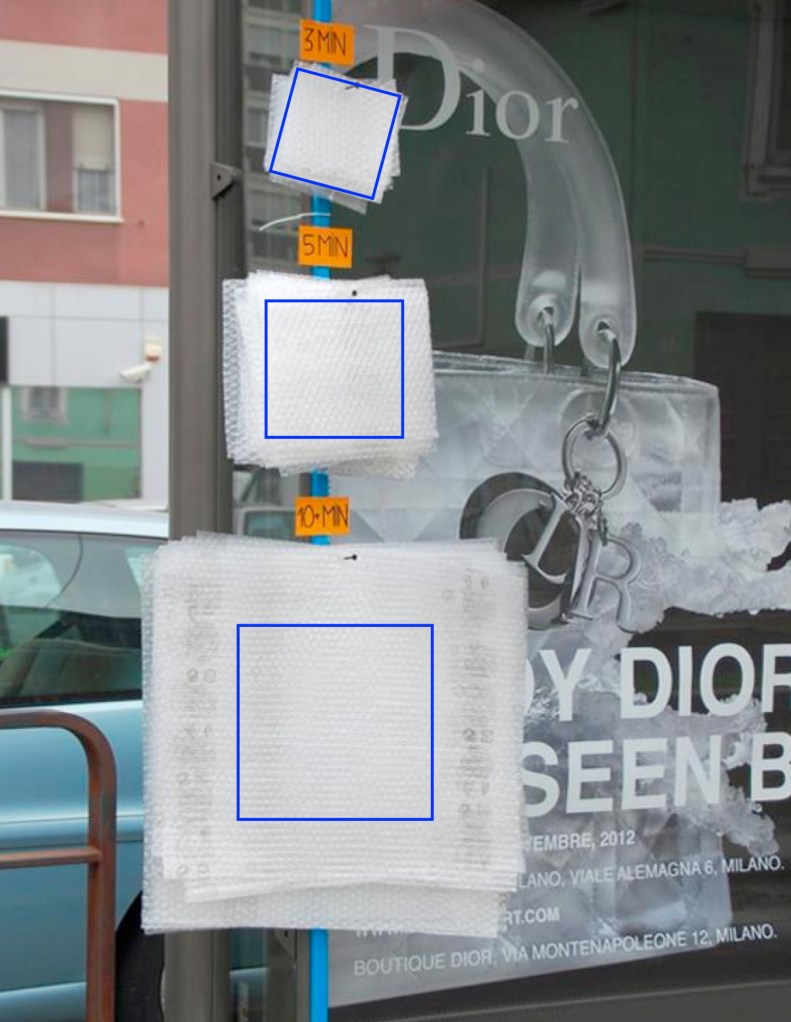

we came up with the following:

After generating a list of possible uses, teachers were asked to plot them in the plane. For example:

Quadrant I: The dynagraphs investigation was placed in the first quadrant (active-understanding). The NCTM Illuminations Pan Balance applet can also be placed here. In this quadrant, learners build depth of conceptual understanding, be it of function relationships or algebraic thinking, through problem solving. Learners encounter many, if not all, of the seven mathematical processes identified in the curriculum. They communicate mathematical ideas, make connections among mathematical concepts and to past experiences, reason and justify their mathematical thinking, and use visualization to make sense of mathematics.

Quadrant I: The dynagraphs investigation was placed in the first quadrant (active-understanding). The NCTM Illuminations Pan Balance applet can also be placed here. In this quadrant, learners build depth of conceptual understanding, be it of function relationships or algebraic thinking, through problem solving. Learners encounter many, if not all, of the seven mathematical processes identified in the curriculum. They communicate mathematical ideas, make connections among mathematical concepts and to past experiences, reason and justify their mathematical thinking, and use visualization to make sense of mathematics.

Quadrant II: An alternate version of dynagraphs was placed in the second quadrant (passive-understanding). The equation is no longer hidden, thereby replacing problem solving with observation. My GeoGebra material also fits here. You know the type: drag a slider (or, worse, watch the teacher drag the slider); what do you notice?

Quadrant III: Ah, yes, Khan Academy. Enough said? Probably not. Activity is limited to pressing pause and rewind. The “intuition” video comes later, if at all. In the third quadrant (passive-knowledge), learners consume content.

Quadrant IV: In the fourth quadrant (active-knowledge), you will find Math Blaster, an iPad app in which students practice math facts (+, −, ×, ÷) through gameplay.

Many interesting comments were made by the group. Some highlights:

“It’s about teaching, not technology.”

Activities can slide from the first quadrant. Who’s doing the math? If it’s the teacher, then we’ve moved to the left. Is the focus on “how-to’s” or essential understandings? If it’s the former, we’ve shifted down. The same holds true for uses of manipulatives.

“We can’t always be in the first quadrant.”

Fair enough. This activity provides one answer to the opening question. Quadrant I is the ideal. Is there value in quadrants two through four? I think so. A demonstration can be helpful. For example, this applet can help learners make sense of A = πr². So, too, can this low-tech activity. Is there a place for grapefruit? There may be. But this can’t be where we live. FWIW, it’s not just that KA occupies this space. It’s that it goes about it so badly. If you must have a grapefruit…

“Your axes are wrong.”

At least one teacher suggested that the x-axis be labelled “active learner.” In Math Blaster, children are active in the sense that they are blasting through razor sharp blockades and speeding past the stars on their HyperCycles. A bit of a stretch to call this active learning. Other possibilities for each axis were suggested: student-centred/teacher-centred, conceptual/procedural, process/content, etc. We fully expected this. The intent of this activity was to generate discussion. The imperfection of our labelling of the axes only added to the conversation. The question “How can technology be best used as a tool for learning mathematics?” became “How do students best learn mathematics?”